Most of the Andre Norton novels I’ve read and reread so far have had issues with being, as we say here, “of their time.” Even when they try very hard to be diverse and inclusive, they’re dated, sometimes in unfortunate ways.

Night of Masks feels amazingly modern. It’s vintage 1964 in its technology (records are kept on tapes, starships are rockets with fins), and there’s only one human female in the book, whose name is a patented Norton misfire: Gyna. But at least she’s a top-flight plastic surgeon, and she performs in accordance with her pay grade; nor is there any reference to her being a second-class human.

The plot is pretty standard. War orphan Nik Kolherne scrapes a living in the slums of the planet Korwar. Nik is the sole survivor of a shipload of refugees that was brought down by enemy fire; he was severely burned, and his face has never responded to such reconstructive surgeries as are available to a person without wealth or family.

The Dipple, where he lives, is controlled by various flavors of organized crime; Nik survives by doing odd jobs and staying out of the way of pretty much everybody, and retreating when he can into fantasy worlds. Until one day, when he happens to overhear an interstellar plot in the works, and is caught before he can escape.

It so happens that the plotters are looking for someone who can play a role in their scheme to kidnap an offworld warlord’s young son and hold him for ransom. Nik is the right age and size, and the offer is one he can’t refuse: a new face. A temporary one for the duration of the caper, with the promise of a permanent one if he gets the job done.

Somewhat ironically, Nik’s role is to play the imaginary friend of the little prince Vandy, complete with fantasy uniform and fantasy tool belt and fantasy name, Hacon. He pulls off the kidnapping of the child from his supposedly impregnable refuge, circumvents Vandy’s conditioning against strangers, and spirits him off Korwar to a very strange world called Dis.

Dis is alien even by Norton-alien standards. Its sun only emits light in the infrared spectrum, which means that humans are blind without “cin” goggles which translate the sun’s light to the visible spectrum. The planet is one of Norton’s postapocalyptic wastelands with unimaginably ancient alien ruins and universally hostile native life, on which the pair’s lifeboat crashes.

The plan is for Nik to win Vandy’s trust, escort him to a rendezvous where he’ll be joined by his contact, Captain Leeds, and extract key information which is concealed in Vandy’s mind beneath layers of conditioning. (Conditioning and brainwashing are a big deal in this universe.)

Vandy is also conditioned, as Nik learns almost too late, to be unable to eat any food but specific types of rations. He can’t eat native foods at all, and even the water is iffy. The point of this is a bit strained, but supposedly it’s about protecting him from kidnapping—none too successfully, and nearly fatally.

Most of the story once Nik and Vandy arrive on Dis revolves around running back and forth to and from a single stash of rations through major obstacles, killer storms, and ferocious monsters. Naturally, this being a Norton novel, a good deal of the running takes place through caves and alien ruins, often both at the same time.

First they have to find a human(oid) refuge, a cave complex built over ancient ruins, but the place turns out to be under the control of a drug-addicted, blue-skinned alien who is not on board with the plan Nik signed on for. Then they have to try to find Leeds, but once he appears, he turns out to be injured and unable to travel far or at speed. Vandy meanwhile keeps taking off, there are never enough cin-goggles which means at least one of them at any one time is blind, and then the Patrol shows up and everything unravels.

By that time Nik has realized that everything he’s been told is a lie, except the part about his face being strictly temporary, and Vandy has caught on to the fact that “Hacon” is an impostor. Luckily, Nik is plucky and resourceful, and as far as his circumstances allow, he has integrity. He does his best to save Vandy from all the different factions who are out to get him.

The end is classic Norton “Oops, running out of page count, gotta wrap it up,” though it’s not quite as hasty as some. Nik delivers the goods to the right set of people, who are not the ones he originally made the deal with—Vandy gets to go back to his father—and as a reward he keeps his face and his job as Vandy’s bodyguard/companion.

What makes this work for me in 2018 is the way the subversive parts are quietly slipped in. Everybody is clearly multiracial: Nik has blue-green eyes and tightly curled black hair, for example, and Vandy and his people are brown-skinned and dark of eye and hair. The humanoid aliens operate as equals of the Earth-type humans, though there is a bit of Morlock-ism in the Disian humanoids, who are described as “degenerate” versions of what must have been the original inabitants.

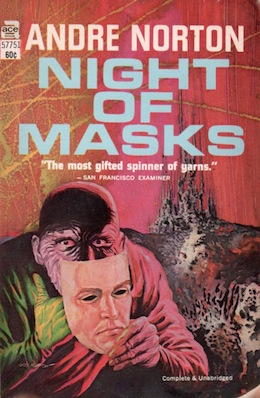

Buy the Book

Night of Masks

And then there’s Nik, whose whole arc is about achieving a new face. The trend in disability activism now is to accept and embrace disability and work to accommodate it rather than focus on curing it, so in that respect Nik’s story is dated. But the fact that Norton constructed a story around a person with a highly visible disability, portrayed him as a rounded person (by Norton standards) with his own life and goals and feelings, and effectively offers representation to readers with similar disabilities, is pretty striking. He’s not presented as “inspiring,” he’s not particularly tragic despite his harrowing history, and he does what he has to do for reasons that make sense in context. Above all, he’s not played for pity, and no one gives him any. He’s just trying to survive.

That’s impressive for the time. So is the almost unbearable timeliness of the universe he lives in, in which war is never-ending, income inequality is drastic, refugees come under attack from all sides, and the poor and disabled get seriously short shrift. It’s a bleak universe, but one that allows its protagonist to fight his way to as soft a landing as possible. There’s a grain of hope in the midst of all.

Next time I’m off on another expedition to the early Sixties: Norton’s 1963 adventure, Judgment on Janus. Another jungle world, another plucky protagonist. More space adventure.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her latest novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.